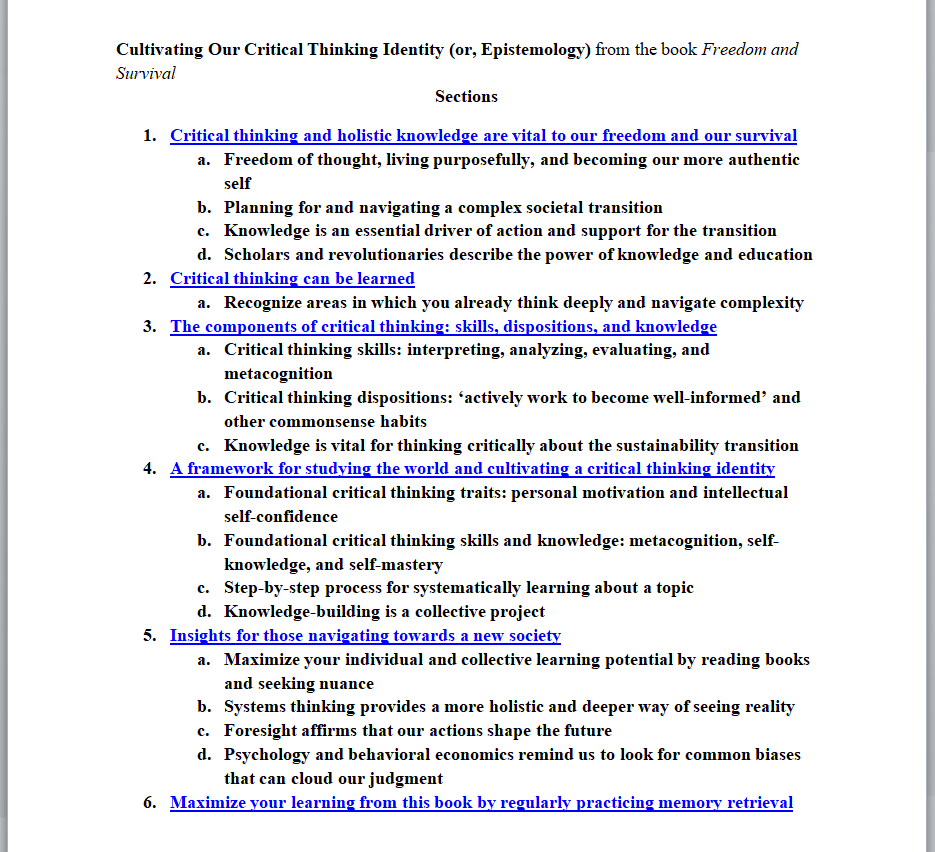

Book Update #1 – Critical Thinking Chapter

In book one of my guidebook series, I am writing about how we can cultivate our intellectual, ethical, and emotional resources to embrace ecological limits and advance the transition towards sustainable and democratic societies.

What topic are you writing about?

I’ve drafted a chapter about why critical thinking and holistic knowledge are essential for making the transition, and how everyday people can cultivate these assets.

Why are you writing about this topic?

I believe that all of us, from those involved in planning an ecological transition to everyday people who will decide whether it moves forward or not, must cultivate our ability to think critically. And not just as a tool we use sometimes, but as a core part of our identity. The essence of critical thinking is an active approach to deciding what to believe, in which we fairly and thoroughly search for and evaluate information about consequential topics. It stands in contrast to a passive approach in which we don’t seek to be informed about important issues or only accept what we happen to hear. We must come to see the active pursuit of knowledge about ourselves and about the world as key to who we are, so that both can be transformed.

The prospects for creating societies that respect ecological limits rest in large part on our ability to successfully perform the massive amount of thinking involved. Wealthy countries must significantly reduce their consumption of energy and materials, with major implications for how their populations live. Beliefs about what technology can or cannot accomplish will shape how (and whether) we prepare for a different future. Political systems, economies, and cultures must shift. Public support depends on our collective ability to navigate complex and contested changes to our societies.

For example, we’ll rely on critical thinking to distinguish real complexity from false complexity. The transition is likely to be more challenging than we tend to hear about, with hard choices to be made about what we preserve and lifestyle shifts we’re not yet prepared for. That’s real complexity we’ll need to navigate. There will also be lots of what I think of as false complexity—propaganda, bad faith arguments, and one-sided perspectives spread by opponents of the transition. We’ll need to be able to tell these two categories apart so that we can plan to productively deal with the real complexity we can’t avoid and not fall prey to the false problems and distractions that will constantly arise.

I also want to help others see how the task ahead demands extensive self-development. One of the big reasons why a transition to a sustainable society could occur despite numerous obstacles is because in many ways it would force us to become a fuller, more authentic, and more capable version of ourselves. We’ll need to develop our ability to think clearly about the world, understand our values, and productively channel our emotions to overcome those obstacles. There is a deep well of fulfillment to be discovered by those working to create this new society.

Another reason I write is to envision and bring into being the kind of group that I want to be a part of. I’d like to belong to a group that embraces complexity and nuance, is actively working to becoming widely and deeply informed, and can have productive discussions about topics that challenge our values. In other words, a group in which each member is committed to cultivating their critical thinking identity in service of both their own personal lives and—just as importantly—in service of the transition towards sustainable and democratic societies. I want to build a movement that is intellectually active and masterful at learning, one whose extensive education and discussion networks evoke the revolutionary salons of the Enlightenment.

I think this chapter can be very useful because it details how anyone with sufficient motivation and time can develop a deep understanding of any topic. It’s the process by which I’ve cultivated the analysis presented in all of my essays. I’ve long felt that a lack of clarity about the consequences of our actions is one of the major roots of most if not all human problems, and I’m hoping this chapter is a resource that can help people learn to think with more clarity.

What are some things you learned or wrote about?

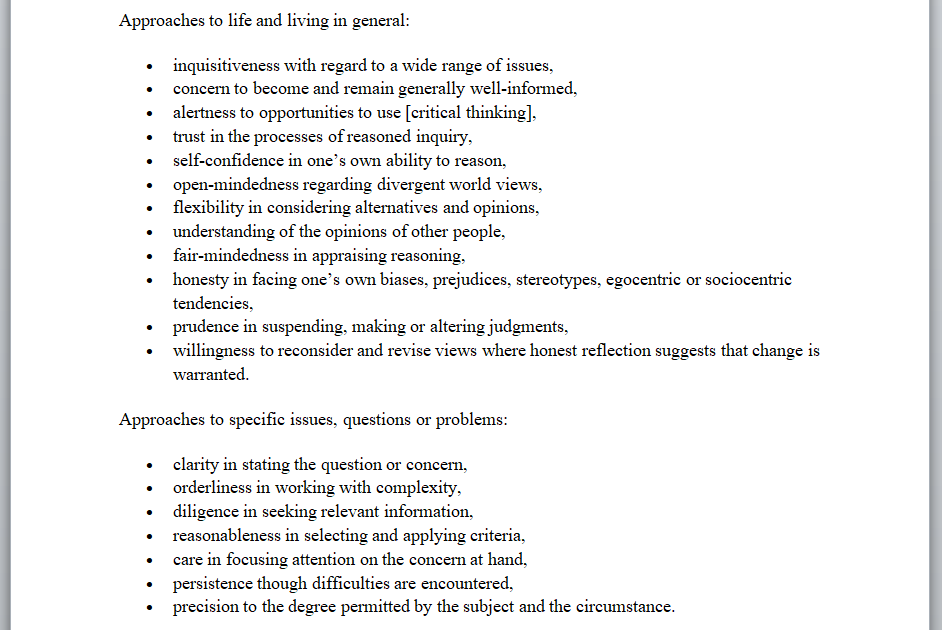

Resources discovered: In 1990, experts in the critical thinking movement were surveyed to find consensus perspectives on the dispositions of a critical thinker (listed below). None of them belong to a small, gifted minority of people, but they do take work to live by. I think we’ll need a movement of people working to build these habits to realize sustainable and democratic societies. (Note: Delphi studies, which directly survey the views of experts in a field, can be a great resource for learning about that particular field.)

Resources discovered: In searching for books on critical thinking, the most practical one I found for applying the associated skills and dispositions in your everyday life is Richard Paul and Linda Elder’s Critical Thinking: Tools for Taking Charge of Your Learning and Your Life. Whereas many of these books seem to get bogged down in technical discussions or emulate a philosophy course in logic, which make the lessons less translatable to real life, this book is geared more for a general reader and is consequently more applicable.

Experts: It can be fascinating and highly informative to not just look for explanations of the ideas you’re trying to learn about, but to trace their history. Alec Fisher offers a concise history of some of the major figures in the critical thinking movement and the ideas they emphasized in his essay “What Critical Thinking Is.”

Insights: Your ability to think critically is as much about being critical of the sources of information you find during your research process as about being critical of yourself. You must ensure you’re searching for and evaluating information fairly and thoroughly, only reaching conclusions that the evidence and assumptions allow, and striving to acknowledge when you don’t know enough.

Insights: It’s common to hear that new (or repeated) information doesn’t change how people think. But if information didn’t change opinions and attitudes, then misinformation wouldn’t be an issue. Indeed, what would be the point of an education system or a media system if information changes nothing?

Insights: We can’t live without trust. We learn the vast majority of our beliefs about the world from what others have done rather than our own direct experience. But who do we place our trust in, and why is that trust justified? It’s a vital question to periodically ask ourselves. One can get extremely far in understanding the world by starting out with a solid “credibility framework” that identifies institutions and people who are likely to make claims about reality in good faith. Alternatively, starting out with a poorly developed credibility framework leads to odd outcomes like getting one’s scientific perspectives from politicians rather than (relevant) scientists, believing evidence-free claims because any rationale (however poor) is provided, or placing trust in figures with an easily searchable track record of making untrue or unreasonable statements.

From the chapter: In this chapter, I highlight nearly two dozen common cognitive biases which could impede the transition if left unchallenged. I describe why each bias presents an obstacle and offer a question we can ask ourselves to try to detect and hopefully avoid its effects. One example is the Ostrich Effect, our tendency to to avoid negative information even if it could help us deal with an issue we have. We’ll need to remain open to all information relevant to effectively planning and navigating the transition. To try to detect whether this sort of bias is influencing your thinking, ask yourself: Am I avoiding information because it makes me feel uncomfortable?

From the chapter: Developing a critical thinking identity is an ongoing process, and it doesn’t make us immune to dealing with problems or making bad choices. It just gives us the best chance of avoiding the problems we can avoid, and for those we can’t, making a better decision than we would have without a critical appraisal of the situation. A society will undermine its own longer-term prospects unless enough of its citizens possess this identity.

From the chapter: Those who want to see reality as clearly as possible must be more committed to holding evidence-based beliefs than to “being right” about the beliefs they currently hold.

From the chapter: The transition towards sustainable societies requires us to become more comfortable with doubt and the unknown because the journey is unprecedented, and because no source, including scientific research, provides absolutely certain truth. The challenge of developing and maintaining trust in one another and in our governments will become even more essential than it is today.

From the chapter: School doesn’t teach us how to systematically analyze the society we live in. That means most of us lack not only the information we’d need to transform our society in a positive way, but also that we don’t see ourselves as the kind of people responsible for deeply analyzing and acting on the big problems facing our society. To create a new society, everyday people must start to see themselves as people who actively learn about the collective problems we face and commit to addressing them.

What’s one takeaway?

Our ability to think critically about a topic depends in large part on possessing knowledge about the topic, argues cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham. For example, everyday people can be empowered to evaluate claims about technology’s role in an ecological transition if they learn enough about technological feasibility. In my view, that’s a crucial and hopeful observation. Critical thinking isn’t simply about the abilities you’re born with. The better you become at learning and the more effort you spend diving into a topic, the more capable you’ll be of thinking critically about it.

If you’re interested in reading a draft of this book and providing feedback, please subscribe here at freedomsurvival.org.

Check out the previous post, which announced this “writing in public” experiment and my goals for this book. Or read the next post, which discusses early work on a chapter about the values of sustainable and democratic societies.

Aaron-

Before I offer my reactions to your latest post, I have a question: Who do y ou see as your target audience? You address your post to “we” who I take to mean those (I include myself here) who are already motivated to “advance the transition to a more sustainable and democratic society”. Those who have already done some homework on the polycrisis facing us and possible means of surviving it and building a new way of life. But there are also in that group those who are more focused and who are actively taking leadership roles in this process(here I do not include myself). Are you trying to influence these folks, too. And then you several times refer to “everyday people”. What do you mean by that phrase?

My first reaction is that I certainly know I need to sharpen my critical thinking. My eyes tend to glaze over when presented with technical material. (I’ll be honest here and say that I started to read some of your previous articles with the word epistemological in the title and didn’t make it very far. And I was a philosophy major.). I wonder if some folks might be put off because they think they already have perfectly adequate critical thinking skills. So I would suggest you provide examples how enhanced skills can help help folks cope. You mention you will describe how you came to see critical thinking as important and how it perhaps changed your life. I think that would be grounding.

My own examples of wishing I had better critical, analytic skills concern 4 projects that I could get involved in in the near future. One is participating in a campaign, backed by a local environmental group, to urge our county to build a new and expensive waste sorting and burning(to produce energy, natural gas) facility connected to the local transfer station. Initially, I have negative feelings about it, but I feel inadequate to the task of studying the issue in depth and thinking critically about it. Another would be an effort, sponsored by a local community rights group, to get a “rights of nature” measure on the ballot. I have more positive feelings here, but again, how to critically evaluate it? Another would be following up on several articles at Resilience.org by Jan Spencer titled “Primer for Paradigm Shift”. (You might be interested in reading these, as they seem to be wanting to accomplish the same goals you have, perhaps in a

Transition Town model). Jan lives in a permaculture lot here in Eugene and I would like to contact him, but again, how to decide if his project is one I want to get involved with.

What I’m trying to get across here is that while on the one hand I welcome an introduction to critical thinking, I’m also a bit scared of “making it a part of who I am”. I don’t know if my reaction is at all typical of a wider audience.

Just in your summary you present a lot of “heavy” stuff. (I just re-scanned your article and I see that you do not say that the chapter on critical thinking would necessarily be the first chapter in the book.). It might be best to start the book with something else( not sure what).

Aaron, I hope that these reactions can be at all helpful. I really am anxious to watch your work progress.

Hi Jere,

Thank you for your thoughtful comment, and my apologies for not seeing it before today.

I’m hoping to write something that is accessible enough for anyone to read, and I have a few audiences in mind. I currently see the main audience for book one (which includes this critical thinking chapter) as people concerned about the ecological crises we face and/or the deterioration of democracy, but unsure of how to help address them. This audience would already believe that these issues are serious enough to take action, and so wouldn’t need the sort of systems analysis I’d provide in book two in order to get started, but could use some analysis and frameworks for engaging in a meaningful way. This audience sounds like it matches the group you belong to. But I also see an important audience being current climate activists looking to build a larger and more effective movement (perhaps the leadership group you described). I think of everyday people as those who have an average amount of social power (i.e. don’t possess immense wealth or political influence) and an average amount of civic inclination (i.e. they don’t consider themselves activists or take much political action beyond voting).

In the chapter, I describe critical thinking as a matter of levels, like lots of things in life. We can continually improve. The current draft of the chapter begins by discussing why critical thinking and holistic knowledge are essential for making the transition to sustainable and democratic societies. Public support depends on our ability to reasonably navigate major questions about our way of life, technological feasibility, ethics, etc. I think that the more people who adopt a critical thinking identity and work on the skills an dispositions involved, the better our chances of realizing the transition. This is both a matter of our individual commitment but also–crucially–developing this identity through collective action and establishing widespread education and discussion networks. I describe the major benefits I get in my life from trying to develop this sort of identity, so hopefully that helps to ground the other arguments as you suggested.

Regarding the projects you were trying to evaluate, I have a few thoughts. First I’d commend you on planning to take action–many people haven’t yet gotten to that stage, so we shouldn’t take for granted how great it is to be prepared to act. I’d say that how you evaluate these projects depends on your overall analysis of what our problems demand and how society must change in general, as well as your ability to gather relevant information about each project (which depends on the quality of your analytical process, your confidence that you can perform that process, the time you have available, etc.). It can take a lot of work to figure out what to do, though we each have our own ideas about when we’ve done enough analysis. Perhaps you can work with like-minded friends nearby to share the intellectual work and collectively answer your questions. You mention how these projects make you feel and whether you feel up to the task of evaluation, and that’s key–emotions play a major role in how we think and what actions we take, and I’m making sure to discuss that throughout the draft of book one.

I’d be interested to hear more about what causes you to feel scared about cultivating a critical thinking identity. Perhaps you can let me know in an email.

Aaron